Fighter Jet News

F-16 Fighting Falcon News

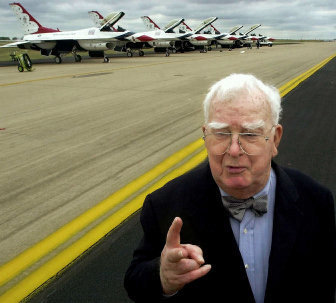

F-16's developer, Harry J. Hillaker, dies at 89

February 10, 2009 (by

Bob Cox) -

It was a chance meeting in a bar with a loudmouthed Air Force fighter pilot that set Harry J. Hillaker on a path that led to the design of the F-16 fighter jet, arguably the best military airplane of the jet age.

Mr. Hillaker, an aeronautical engineer at General Dynamics for 44 years and known to many as the "Father of the F-16," died Sunday at his home in Fort Worth. He was 89.

As a senior engineer at General Dynamics' Fort Worth aircraft plant in the 1960s, Mr. Hillaker led a design team that worked, secretively at first, with a small group of Pentagon insurgents to turn a collection of ideas, theories and concepts into what would become the F-16.

Their success is evident in that four decades later, the plant, now part of Lockheed Martin, is still producing F-16s. More than 4,400 have been built and delivered worldwide. At the peak of production in the 1980s, close to 25,000 people were working on the program.

"Harry's legacy is an incredible aircraft that has become the mainstay of 25 nations and continues to be in demand today after 30 years of production," said Ralph Heath, president of Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Co. "The early F-16 versions paved the way for tens of thousands of jobs, over $100 billion in sales and customer relationships that are the cornerstone for Lockheed Martin's transition to the future with our new aircraft programs."

Any success has numerous fathers, and the F-16 is no different. But people close to the F-16 program say Mr. Hillaker's engineering expertise, open-mindedness and loyalty to a concept originally known simply as the "lightweight fighter" were critical.

"Without Harry, I don't think anything close to the F-16 would have come to fruition," said Jay Miller, an Arlington aviation historian.

Mr. Hillaker, born in Flint, Mich., and educated at the University of Michigan, went to work for Consolidated Aircraft in San Diego in 1941. A year later, he was sent to the company's Fort Worth plant. With Consolidated, which became General Dynamics, Mr. Hillaker worked on most of the company's major projects, including the B-36, B-58 and F-111 bombers built in Fort Worth.

One night in 1962 at the Eglin Air Force Base officers club, Mr. Hillaker was introduced to Maj. John Boyd, an abrasive and cocky but highly intelligent fighter pilot. Informed that Mr. Hillaker had worked on the F-111, then under development, Boyd launched into an expletive-laden tirade about what a poorly designed, underperforming aircraft it was fated to be.

According to numerous reports of that meeting, Mr. Hillaker quickly realized that Boyd knew far more about airplane design and performance than most pilots and invited him to sit. Soon, the two men were exchanging ideas and formulas on cocktail napkins.

In the years that followed, Boyd, assigned to the Pentagon, argued the cause for a lightweight, highly maneuverable and affordable fighter plane, the polar opposite of the F-111. He gained a few adherents, notably fellow fighter pilot Col. Everest Riccioni and a civilian Pentagon official named Pierre Sprey.

The Fighter Mafia, as the three became known, concocted a scheme to covertly begin work on just such a plane. Covert, because top Air Force brass were largely opposed to the concept and were spending billions to develop the new F-15 jet.

In 1969, Riccioni wrote a vaguely titled budget request and received $149,000 for performance and design studies. General Dynamics and Northrop were selected to work on competing design concepts.

Mr. Hillaker, who since getting to know Boyd had quietly guided some internal lightweight fighter design work, was General Dynamics' point man for the program. On numerous occasions over the next two years, he secretly flew to Washington and met with Boyd, Sprey and a few others to hash out theories and share data and design concepts.

"We used to stay up all night arguing about performance and trade-offs," Sprey said. "He gave us a lot of insights both into design and General Dynamics internal politics. He was committed to doing it right."

Mr. Hillaker, Sprey said, meshed well with the mercurial Boyd and "was very open-minded. Among designers in the aircraft business, that was very rare."

The lightweight fighter incorporated a number of advanced technologies, in particular fly-by-wire controls, all aimed at making it the most agile and lethal aircraft and capable of winning one-on-one dogfights against the best Soviet-bloc aircraft of the day.

Top civilian Pentagon officials, at the urging of Boyd and Sprey, eventually gave their blessing to the program, and contracts were let for each team to design and build prototypes. A fly-off, under stringent conditions demanded by the Fighter Mafia, was held in 1974.

General Dynamics' YF-16 was a clear-cut winner over Northrop's YF-17. Sprey says Mr. Hillaker and his team were due a large share of the credit.

"I can practically run down the things that wouldn't have been in the airplane if it wasn't for Harry," Sprey said.

Mr. Hillaker went to hold several positions with General Dynamics and to further develop the F-16. He retired in 1985 but remained active with numerous aerospace organizations and advisory groups.

As a senior engineer at General Dynamics' Fort Worth aircraft plant in the 1960s, Mr. Hillaker led a design team that worked, secretively at first, with a small group of Pentagon insurgents to turn a collection of ideas, theories and concepts into what would become the F-16.

Their success is evident in that four decades later, the plant, now part of Lockheed Martin, is still producing F-16s. More than 4,400 have been built and delivered worldwide. At the peak of production in the 1980s, close to 25,000 people were working on the program.

"Harry's legacy is an incredible aircraft that has become the mainstay of 25 nations and continues to be in demand today after 30 years of production," said Ralph Heath, president of Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Co. "The early F-16 versions paved the way for tens of thousands of jobs, over $100 billion in sales and customer relationships that are the cornerstone for Lockheed Martin's transition to the future with our new aircraft programs."

Any success has numerous fathers, and the F-16 is no different. But people close to the F-16 program say Mr. Hillaker's engineering expertise, open-mindedness and loyalty to a concept originally known simply as the "lightweight fighter" were critical.

"Without Harry, I don't think anything close to the F-16 would have come to fruition," said Jay Miller, an Arlington aviation historian.

Mr. Hillaker, born in Flint, Mich., and educated at the University of Michigan, went to work for Consolidated Aircraft in San Diego in 1941. A year later, he was sent to the company's Fort Worth plant. With Consolidated, which became General Dynamics, Mr. Hillaker worked on most of the company's major projects, including the B-36, B-58 and F-111 bombers built in Fort Worth.

One night in 1962 at the Eglin Air Force Base officers club, Mr. Hillaker was introduced to Maj. John Boyd, an abrasive and cocky but highly intelligent fighter pilot. Informed that Mr. Hillaker had worked on the F-111, then under development, Boyd launched into an expletive-laden tirade about what a poorly designed, underperforming aircraft it was fated to be.

According to numerous reports of that meeting, Mr. Hillaker quickly realized that Boyd knew far more about airplane design and performance than most pilots and invited him to sit. Soon, the two men were exchanging ideas and formulas on cocktail napkins.

In the years that followed, Boyd, assigned to the Pentagon, argued the cause for a lightweight, highly maneuverable and affordable fighter plane, the polar opposite of the F-111. He gained a few adherents, notably fellow fighter pilot Col. Everest Riccioni and a civilian Pentagon official named Pierre Sprey.

The Fighter Mafia, as the three became known, concocted a scheme to covertly begin work on just such a plane. Covert, because top Air Force brass were largely opposed to the concept and were spending billions to develop the new F-15 jet.

In 1969, Riccioni wrote a vaguely titled budget request and received $149,000 for performance and design studies. General Dynamics and Northrop were selected to work on competing design concepts.

Mr. Hillaker, who since getting to know Boyd had quietly guided some internal lightweight fighter design work, was General Dynamics' point man for the program. On numerous occasions over the next two years, he secretly flew to Washington and met with Boyd, Sprey and a few others to hash out theories and share data and design concepts.

"We used to stay up all night arguing about performance and trade-offs," Sprey said. "He gave us a lot of insights both into design and General Dynamics internal politics. He was committed to doing it right."

Mr. Hillaker, Sprey said, meshed well with the mercurial Boyd and "was very open-minded. Among designers in the aircraft business, that was very rare."

The lightweight fighter incorporated a number of advanced technologies, in particular fly-by-wire controls, all aimed at making it the most agile and lethal aircraft and capable of winning one-on-one dogfights against the best Soviet-bloc aircraft of the day.

Top civilian Pentagon officials, at the urging of Boyd and Sprey, eventually gave their blessing to the program, and contracts were let for each team to design and build prototypes. A fly-off, under stringent conditions demanded by the Fighter Mafia, was held in 1974.

General Dynamics' YF-16 was a clear-cut winner over Northrop's YF-17. Sprey says Mr. Hillaker and his team were due a large share of the credit.

"I can practically run down the things that wouldn't have been in the airplane if it wasn't for Harry," Sprey said.

Mr. Hillaker went to hold several positions with General Dynamics and to further develop the F-16. He retired in 1985 but remained active with numerous aerospace organizations and advisory groups.

Published on February 10, 2009 in the Star Telegram.

Republished with kind permission of Bob Cox

In Memoriam

Additional images:

Related articles:

Forum discussion:

Tags

- YF-16 turns 30 (2004-02-02)

- F-16 Fighting Falcon news archive

Forum discussion:

- Rest in Peace, Harry ( 9 replies)

Tags